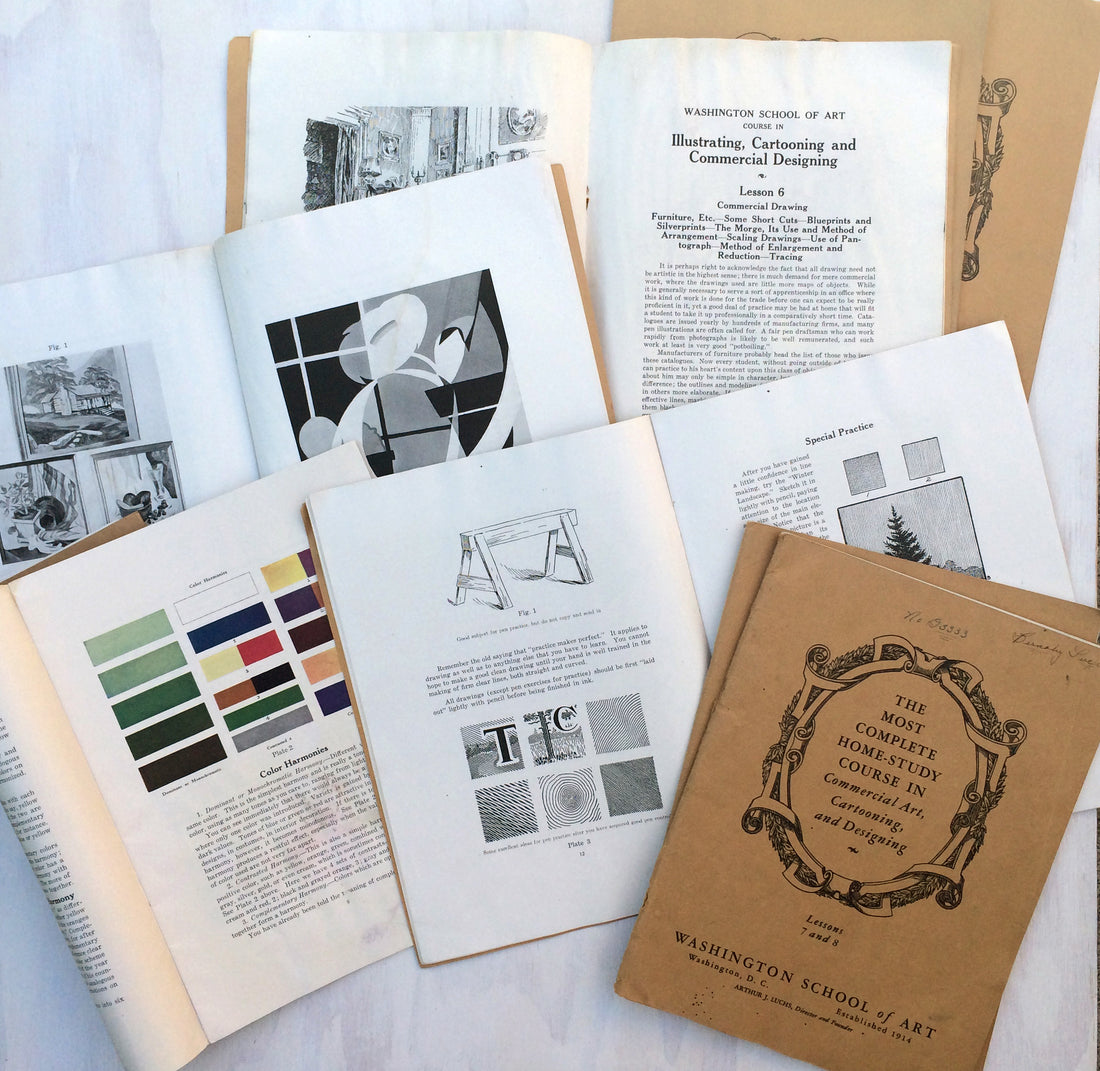

Last summer my mom found these books while clearing out my Grandma’s house. Like many people who grew up poor and during the Great Depression, my Grandma Martha was definitely a saver. She kept so much useless AND great stuff for future need or to be able to help someone else. Sadly, she didn't get to disperse of her good deeds as much as she may have wanted before dying but I feel like these books are a gift from the grave.

As a graduate of art school with a degree in Commercial Art and lover of old ephemera, my mom knew I’d like these textbooks. We both thought they were unusual but not that strange in the giant mix of things my grandma would keep.

Then one day while my mom and I were discussing the finer details of the the lesson books over the phone, I discovered THE LETTER. OMG. I quickly scanned it and then read aloud the revelation that these books had belonged to my Grandfather, Bernabe Lucero (1917–1999.) My mom had not seen the letter tucked inside one of the books before sending them to me in California.

This School of Art letter is a masterpiece of antique business language and encouragement. The closing is my favorite part: “But we, too, shall want to share a little of your joy because we are going to do our very best to help you get the results you want– results that will make your life a little richer– a little less difficult and far more pleasant! Don’t slacken! Don’t stop! Just keep right on moving ahead!” What genuine support and recognition of a challenging time for this budding artist, and maybe even the world, at that time when it was really tough to make a steady income.

In 1936 my grandfather was 19 years old and living in the very poor, tiny town of Chamisal, New Mexico (pop. 300 in the year 2000) when he received this letter from the Art Instructor. Wait? My maternal grandfather had wanted to be an artist? And a commercial artist at that? It took me a moment to fully absorb this information. I had always known him as the master carpenter of Taos county. So many people over the years had told me of his skill and fortitude in homebuilding and I’d seen many of the cabinets and other pieces of humble and functional furniture he had built for himself and others.

Most likely, my grandfather found his way to this particular type of art school by a tiny magazine ad that was still popular in my childhood: "Draw Me." Audrey Watters of Hack Education blog wrote this insightful article about this early model of distance learning and it's thought-provoking, modern-day counterparts. From her article: "By 1926 there were over three hundred such schools in the United States, with an annual income of over $70 million (one and a half times the income of all colleges and universities combined), with fifty new schools being started each year. In 1924 these commercial enterprises, which catered primarily to people who sought qualifications for job advancement in business and industry, boasted of an enrollment four times that of all colleges, universities, and professional schools combined." And sadly: "He cites a 1926 survey that found that just 2.6% of students completed the correspondence courses they enrolled in. Sound familiar?"

Correspondence schools offered home study for someone who loved to draw that may have been from a rural and/or disadvantaged life. I learned that back-in-the-day such a course would have cost between $75–$100, whereas attending an art school offering a similar education would have cost around $400. The instructors were working commercial artists hired to review and offer critique for the correspondence students and act as a mentor for an education that had no set timeframe. Can you imagine the delight in receiving a letter from your correspondence teacher and the relationships that developed from this unique education?

Steven Heller wrote this excellent article about these Schools in 2008 for The Design Observer.

The lessons in these books are well-written, demonstrate perfect examples of creating illustrations and lettering for the limited reproduction techniques of the day and provide useful instruction for ways to develop an artist’s skill by observation and repetition. Unfortunately, they also describe an ignorance and racial prejudice of the time. I cringe that people of color received the assignment to draw a “character of a negro minstrel.” There are a lot of stereotypes in drawing politicians and hobos but also the encouragement that women could be a part of this industry!

Here, I wish I had a piece of my grandfather’s art from a course assignment to share, but instead I present this chair he built that I treasure.

PS1: I grew up in a very creative family and will share next about my parents and their art practices.

PS2: Please sign up here to receive my monthly newsletter with alerts to new blogposts, newly completed illustration work and other offerings. Thank you!